According to the Times Online, copyright protection for Popeye the Sailor is going to expire at the end of 2008. Under EU rules, copyright protection lasts for 70 years after the death of the author. Popeye creator Elzie Segar died in 1938 at the age of 43, making Popeye the first iconic cartoon character to fall out of copyright.

This means that Segar's artwork can be reprinted in Europe without permissions. Here in the U.S., we have to wait until 2024 for Popeye's copyright to expire, which explains why I didn't use a picture for this post. It should also be noted that Popeye is registered as a trademark in a number of international classes, so think twice before trying to register Popeye brand spinach, or really anything else for that matter, anywhere in the world.

Popeye's release from copyright protection will be an interesting test for what will happen when other major cartoon characters enter the public domain. Barring another successful lobbying campaign, Disney will see Mickey Mouse come into the public domain in 2023.

Happy New Year!

Wednesday, December 31, 2008

Popeye in the public domain (in Europe, that is)

Saturday, December 20, 2008

You know you're big when someone tries to trademark your name

And now, the latest news from the intellectual property in sports desk: NFL quarterback Vince Young is suing three individuals who have tried to register his nicknames, "VY" and "Invinceable," with the USPTO. According to USA Today, Young's lawyer has said that the trademark registration has stood in the way of a deal with Reebok, who was apparently interested in marketing some "VY" merchandise.

I checked it out on TESS and, sure enough, the mark is currently registered. (To see for yourself, go to the uspto.gov website, click on trademarks on the left side, and then click on TESS, the third option down. Enter the mark in the "New User Form Search.")

For an enlightening discussion of the ins and outs of using personal names as trademarks, check out the latest edition of Stephen Elias and Richard Stim's Trademark: Legal Care for your Business & Product Name. (That link is to the eBook, which requires a library card to log in. If you don't have one and you're a California resident, you're in luck: SFPL has a brand-new eCard, which gives CA residents access to thousands of online resources. Learn more about it here.)

Trademark woes aside, it must be quite an ego-booster when somebody feels that your name or nickname is valuable enough to merit a trademark registration!

Friday, December 19, 2008

Take it from the agency -- 3 great free publications from the USPTO and the Copyright Office

The way that laws and regulations is written is extremely important. If the wording is imprecise, enterprising people find loopholes and, before you know it, the intent of the law is undermined. Our Federal goverment has a couple of hundred years' experience creating the kind of air-tight prose that holds up to scrutiny, and while this kind of language is important for those interested in the law, it's almost always incomprehensible for those poor folks (call them laypeople) who have to try to do some kind of business with the government.

The commercial publishing industry certainly has picked up on the market for people who want help dealing with the government, and many of the millions of people each year who want to apply for a patent or register a trademark or copyright get some help using titles from NOLO Press, Sphinx, Oceana, and other publishers.

It's worth noting that, in addition to commercially produced guides to intellectual property, the agencies themselves (in this case the USPTO and the US Copyright Office) have done an excellent job of creating materials to educate the public about these areas of law. Although commercial publishers have the advantage of being able to offer subjective legal advice to readers, the agencies themselves are the most authoritative source for information about intellectual property. Below are just three examples of publications that I find particularly useful:

Copyright Circular 1: Copyright Basics

United States Copyright Office

There are some people who need lots of detailed information about copyright in the U.S. Attorneys, for instance. Or artists who plan to use someone else's work or prevent someone else from using their work. Recording industry executives seem pretty interested in our copyright law, as do some Members of Congress. For these folks, there are mountains of materials, published by commercial, academic, and government presses, covering laws, legislation, case history, trends, etc. in the field of copyright.

For the rest of us, there's a wonderfully concise series of publications, called Circulars, that come to us courtesy of the U.S. Copyright Office. There are a couple dozen of these things, covering pretty much every matter of business most folks will ever have with the Copyright Office. I'm not promising a riveting read (example: Circular 4oA, Deposit Requirements for Registration of Claims to Copyright in Visual Arts Material). I do think, however, that in an information environment rife with misinformation (I'm referring to the Internet), it's extremely important to have reliable, authoritative information about legal topics. Copyright Circular 1 is just that. It's readable, informative, comprehensive, and pretty darn concise considering the breadth of the subject matter that it covers. This is an excellent place to begin any copyright research.

A Guide to Filing a Utility Patent Application

US Patent and Trademark Office

David Pressman's Patent it Yourself is probably our most popular guide to filing a utility patent. One of the major selling points of the book is Pressman's direct, no-frills writing style. It's a testament to the complexity of the patent system, then, that such a concise writer still requires 572 pages (in the latest edition) to demonstrate how to get a patent.

A Guide to Filing a Utility Patent Application, the USPTO's consumer patent application pamphlet, is 16 pages long and is, arguably, as indispensable for fledgling patentees as Pressman's book. How? It's written in haiku (not true). The pamphlet is actually short simply because it contains a lot less information than Pressman's book does. It is, however, still very useful because it contains the very basic facts about what patent examiners expect from a utility patent application in one short, direct, and authoritative volume.

Think of it this way: Will the Periodical Table of the Elements tell a layperson everything about chemistry? Of course not. But, when used alongside other, more expository texts, it is an essential reference in that field. Same goes with A Guide to Filing a Utility Patent Application. Here at the library, we keep copies on hand for quick reference.

(By the way, if you want to know everything there is to know about U.S. patent prosecution, I refer you to the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure, all four inches (thickness, that is) of small print and tissue-thin paper.)

Basic Facts About Trademarks

US Patent and Trademark Office

There are few trademark questions that come across our reference desk that have an answer that cannot be found in the USPTO's Basic Facts About Trademarks. Should I register my mark? Page 1! How do I submit a colored drawing? Page 6! How long does my registration last? Page 14! There's even a current International Schedule of Goods and Services on pages 16-17. Basic Facts does for trademark researchers what A Guide to Filing a Utility Patent Application does for wannabe patentees; that is, it acts as a starting point, an unassuming collection of the facts essential to a basic understanding of the trademark process.

The USPTO did us all a favor by adopting a question-and-answer format for this brochure, and that, to me, is what makes it stand out among trademark informational brochures, of which there are many. Most of us who are using trademark informational brochures don't know the first thing about trademarks. Though we may have a specific question that brings us to the brochure, we may notice another question that we didn't even know we had. Intent to use? Tell me more! Also handy is the "trademark, patent, or copyright?" segment at the very beginning of the brochure, which can save the true new-comer the trouble of exploring the wrong avenues of intellectual property.

There's much more available from the agencies that you can access for free by visiting the USPTO and Copyright Office websites, or by stopping in to see us at the public library.

Friday, December 12, 2008

Update: Another piece of the trademark search puzzle, available here at the library

Update, 8/25: Trademarkscan was many things to many people, but one thing that it wasn't, at least at the San Francisco Public Library, was popular. I'm sorry to report that TMScan is no longer available at the Patent and Trademark Center. Please get in touch if you're interested in learning about alternative approaches to state TM searching.

Original post:

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A proper trademark search can be quite a puzzle, particularly because there is no one central place to find the information. Though there is a Federal trademark registry that's pretty easy to work with, the USPTO does not have a monopoly on trademark registrations. As I've mentioned in a previous post (and as I'm realizing I should write about in more depth in the future), a mark doesn't necessarily have to be registered with the USPTO to be enforceable. Remember, the purpose of a trademark is to help consumers identify products and services. It follows, then, that a longstanding mark associated with a particular enterprise may have some protection, regardless of registration status.

What's best for consumers isn't necessarily good for trademark searchers, however. To research a mark that's intended for use across the country, a Federal trademark search is a good start, but there are a couple of other elements that a completist searcher will want to consult. The first, a common law trademark search, can be done using a few resources that the Business, Science, and Technology department here at the library has. You can read about that here.Another component of the search process is finding marks registered in individual states. Many businesses only operate within a particular state, and in those cases, registration within that state may be sufficient. A trademark registration in a particular state may interfere with use of the mark within that state, so it's wise to check state trademark registries as part of a trademark search. You can check each state individually -- to search California trademarks, for instance, visit the Secretary of State's website -- but, for those able to come into the library, we have a tool that allows one-stop shopping for state trademark registrations. It's called Trademarkscan, and it's a for-pay database that you can use for free at the library. Using Trademarkscan, you can perform a search across all fifty states of registered trademarks. If you have a mark that you think that you may want to use in several states, this could be a real timesaver for you.

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

"Gobble up some of these a-maize-ing patents and trademarks"

For your Thanksgiving enjoyment, I refer you to the USPTO's Kid's Pages to feast (I love puns as much as the USPTO does) on some patents and trademarks from their files.

For your Thanksgiving enjoyment, I refer you to the USPTO's Kid's Pages to feast (I love puns as much as the USPTO does) on some patents and trademarks from their files.

Most of the patents are turkey-related, though a few, like this gravy separator, are ostensibly vegetarian-friendly.

While you're there, take a look at some of the other features in the Kid's Pages. If you have kids, work with kids, or are a kid, you may find yourself thankful that the Department of Commerce put so much into these pages.

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

USPTO Annual Report for FY 2008 shows record

The USPTO released their annual report for FY 2008 yesterday, and boy was it a doozy. Here are some highlights from their press release:

Patents – Optimizing Patent Quality and Timeliness

In FY 2008, USPTO met and, in some cases, exceeded its patent pendency, production, and quality targets. Patents maintained a high level of patent quality by achieving an allowance compliance rate of 96.3 percent, exceeding its goal.

- Patents increased production by an additional 14 percent over FY 2007 by examining 448,003 applications—the highest number in history. Production has increased by 38.6 percent over the past four years, compared to a 21.3 percent increase in application filings during the same period.

- Patents received a record number of utility patent applications filed electronically (332,617), and achieved a record rate (72.1 percent) of applications filed electronically as well.

- Patents achieved an average first action pendency of 25.6 months and an average total pendency of 32.2 months.

- Patents received 1,765 patent application filings through the Accelerated Examination Program, 173 percent more than in the program’s introductory year of FY 2007. A 12-month or less pendency rate was also maintained for every application, with an average time to final action or allowance of 186 days.

Trademarks – Optimizing Trademark Quality and Timeliness

For the third year in a row, USPTO met or exceeded all of its performance goals for trademarks as well.

- Trademarks ended its year with first action pendency at three months. Trademarks has maintained its first action pendency within the 2.5 to 3.5 month range for more than 18 months, a historic first. Disposal pendency was also maintained at record low levels, ending the year with 11.8 months pendency for cases without inter partes or suspended cases and at 13.9 months for all disposals. This disposal pendency is the lowest in 20 years.

- This year saw a record number of applications filed electronically--approximately 268,000 applications comprising 390,000 classes. This represented a record rate of filing; 96.9 percent of all applications were filed electronically.

- Quality remained high throughout the year with a first action compliance rate of 95.8 percent and a final action compliance rate of 97.2 percent. Both measures exceeded performance expectations.

That's right, '08 saw records in both patent applications and electronic trademark applications.

View the full report here.

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Trademarks:Some tips for searching for images at the USPTO

Based on my experience helping people at our reference desk, I would argue that images are perhaps the greatest source of confusion for fledgling trademark searchers. I suspect that this is because the predominant 21st Century searching habit -- namely, keyword searching -- relies on matching words directly rather than filtering words through an index. Given the amount of information available through the Internet, keyword searching works just fine to call up text-based resources, but it really falls short when it comes to non-text information like pictures. Image searching through popular search engines is OK when you quickly need a picture of, say, an ostrich pulling a cart, but for a legal need like a trademark search, when a business' identity (not to mention a lot of money!) is at stake, something more reliable is necessary.

Anyone familiar with the United States Patent Classification understands just how seriously the USPTO takes their indexing. And for the same reasons patent searchers must take the time to learn the USPC, a person eager to perform a comprehensive trademark search at the USPTO would do well to learn how to use the trademark Design Search Code Manual.

Every trademark that is based on an image is assigned a Design Code (DC) at the time of registration. Once registered, those marks are available through the Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS) and are searchable through that DC that an examiner assigned. To find marks containing a specific image, a searcher can find the corresponding DC number using an online version of the Design Search Code Manual (sorry, no acronym for this one).

That's a mouthful, I know, but it's really more simple than it sounds. The idea is that you can look up words that describe what your image is, match those words to the appropriate DC number, then look up that number in the trademark database to inspect other marks that have that DC number.

Let's say, for example, that I have a line of gardening gloves. I call them Moose Gloves and I've had a gifted artist create this logo as my brand:

Using TESS, I can search for the words that I plan to use in my mark, but I also want to make sure that I catch any similar images before I send the application. To do this, I'll consult the Design Search Code Manual. Under "M," I scroll down until I see moose (that's what the drawing is, by the way). The Manual tells me that the DC number for moose is 03.07.07.

If you're not entirely sure that a DC number adequately describes your image, you can click on the number to get examples. I should also mention that the Manual is pretty comprehensive and includes codes for geometric shapes, celestial bodies, mythological figures, ethnic groups -- if you can imagine the variety of trademarked images you've encountered in your life, just think that there's a DC number assigned to each.

To continue with our example, now that I have a DC number for my moose, I can go to TESS, choose the "structured form search," then enter the number (without punctuation, so my moose would be "030707"). In the drop-down menu in the field box, choose Design Code. If you want to narrow the results of the search, you can also enter a US class number in the second search box. (Class numbers are found using the Trademark Acceptable Identification of Goods and Services manual, which you can access online here.) If you do enter a search term in the second box, make sure to change the operator, on the right side of the screen, from "or" to "and."

When you click search, this will bring up a list of all, if any, registered marks that match your search. To browse the images that came up from your search, look for a blue button at the top of the screen that says "image list." Clicking this will bring up just the images in a way that makes it easy to scroll through and look at your search results.

None of the artwork that came up from my search were of the same caliber as my moose, so it looks like I'm safe. Remember that, as always, the idea is to have a mark that is not confusingly similar to another mark in the same class. Happy hunting!

Sunday, November 9, 2008

New in the Patent and Trademark Center -- Gifts for the inventor in your life

The magazine is currently on display in the Patent and Trademark Center at the Main Library.

Saturday, November 1, 2008

Software and business method patents are on the rocks

On Thursday,the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled against Bernard Bilski, a man whose patent for a method of reducing risk in commodities trading was ruled invalid by the Board of Patent Appeals. For Bilski, this means that he only has one more place to bring his appeal (the Supreme Court). For the rest of us, this establishes a much more narrow interpretation of patentability for software and business method patents.

Software and business method, popular with internet companies, came into vogue after the 1998 State Street Bank case in which the court ruled that any method that had "useful, concrete and tangible results" could qualify for a patent. With the Bilski ruling, there's a new patentability test in town -- "machine-or-transformation." For a software or business method patent to be legit, it must now be either attached to some machine or device or it must transform something into a different state.

There's a pretty good summary at the Patent Law Blog here. Here's a shorter summary from Reuters.

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

Lessig on copyright and political speech

Sure, he may have moved on to new, non-copyright related projects, but that didn't stop Lawrence "Mr. Creative Commons" Lessig from speaking up in the New York Times last week about what he sees as a misuse of copyright by overcautious media outlets. Click here for the NY Times website or here to read it without ads through the library's subscription. (Library card required).

Friday, October 24, 2008

Open source hardware

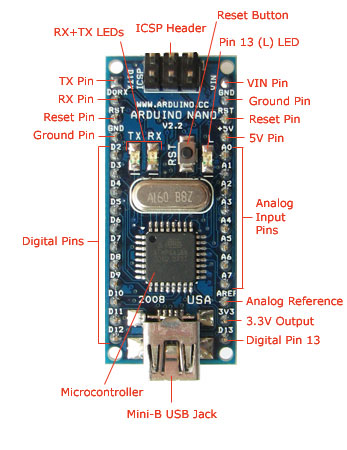

Wired magazine, in addition to suffering from what can only be described as an obsession with the iPhone, often publishes very thoughtful and thought-provoking pieces about intellectual property trends. Chris Anderson, the editor-in-chief at the magazine, did in fact recently come by the library to give a talk to some staff members, and he spoke about some of his ideas about intellectual property. Considering the editorial big cheese's interests, it wasn't a surprise to me that this month's issue of his magazine features an article about open source hardware, an idea that fits in well with his words about copyright. The article is about a company called Arduino. They make circuit boards. Find the article here.

Open source hardware is a fascinating idea, and one that I think really gets to the heart of what the patent system is all about. While the monopoly that a patent owner is given is often the focal point of the patent process, it's really secondary, at least in the interest of the public, to the development of technology. Giving an inventor control of the market for an invention is merely an incentive, a carrot to encourage technological development. The practice of publishing patents exists as a way of disseminating technological knowledge; people aren't free to manufacture patented products, but they are free to try to improve on the technology. Taking out the monopoly only makes it easier for people to tinker with the invention, and thus makes that invention a greater good to the public.

It's kind of exciting for me to think of an army of volunteer engineers across the world collaborating on a project that anyone can use. Whether the spirit of voluntary innovation that has made Linux and Wikipedia successful can carry over to the manufacture of physical objects like circuit boards, no one can say. If Arduino's business model of giving away the secrets works, however, the impact on the future of commercial technological development could be pretty huge.

During his talk at the library, Anderson argued that it was in his interest as an author to have his words reach as large an audience as possible, and that the best tactic for spreading his writing is to give it away. Using that model, his profit would come from increased recognition, which, in turn, would lead to increased demand for his expertise (most likely speaking engagements in the case of an author).

It looks like the open source hardware folks are using a similar model. As the inventors of their product, any buzz that the product generates will center on them. People will then seek them out for consulting work, or as the authoritative manufacturer of the product. It will be interesting to see how successful this venture is and if that model catches on.

In the mean time, patent application statistics are on the rise, so don't expect the end of patents to come any time soon, though if the Creative Commons process could be applied to hardware, I wonder if we will soon be seeing more "share-alike" licenses for patented technology. Perhaps there's room for that in the 21st Century.

Thursday, October 16, 2008

New in the Patent and Trademark Center (kind of): some magazines

Tucked away in a little corner of the fifth floor of the Main Library, the Patent and Trademark Center is some really prime real estate. Insulated from the activity of the reference desks and the atrium, people who discover the room can enjoy reading by the sunlight coming through the same windows that look down over the UN Plaza (and the farmer's market on Wednesday and Sunday) and the Asian Art Museum. It's a comfortable, quiet, lovely place to be.

Admittedly, there is a bit of contrast between the warmth of the room and the, eh, clinical, nature of most of the material in there. We have a bunch of Indexes to Patents, lots of three-ring binders, and, of course, a couple of computers for CASSIS and the USPTO website. Some of the commercially published books we have in there are pretty interesting -- some histories of invention and technology, a couple of "wacky patent" type books, some popular guides to intellectual property -- but, for the most part, the reading material in the Patent and Trademark Center is all business.

Every once in a while, however, something more broadly appealing than, say, American Marking Gages comes along, something that (no offense to the hardworking author of the above title) could be of interest to a general audience. When that happens, I'd like to use this space to put the word out, so look out for the "New in the Patent and Trademark Center" posts to find out when fun, beautiful, or particularly interesting materials arrive. It doesn't happen very often, but you may be surprised by some of the things we get.

In the spirit of promoting some of our material, I'd like to present a couple of magazines that we subscribe to. We've had some subscription issues that caused a lapse in service, but the problems seem to be resolved and we are now receiving issues of surprisingly interesting titles, including the following:

American Heritage is a history magazine; American Heritage's Invention & Technology is about the history of, you guessed it, inventions and technological advances. It comes to us quarterly full of thoughtful writing about technology and great photos, both original and archival. Features in this summer's issue include a piece about the cameras on the Mars rover, innovations in gold mining, and a high-drama look at the early days of cinema.

Inventor's Digest's self assessment as "the magazine for idea people" is apt -- though centered on the needs and interests of inventors, the magazine transcends the narrow inventor audience by covering the culture of invention and inventors in a format that looks more like People than like wonky trade journal. There is plenty here for inventors and non-inventors alike. The November issue has tips on finding money to market inventions, connecting with large corporations to create business partnerships, and plenty of profiles of people making their ideas work for them.

It may not occur to you that a massive intergovernmental organization such as the United Nations would publish glossy magazines, but the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the intellectual property arm of the UN, puts out a handsome title called WIPO Magazine. It comes to us monthly and covers trends and happenings coming out of the increasingly important world of international intellectual property. The August issue (there's a bit of a lag because it comes to us free through the USPTO depository program) includes articles about the Chinese film industry, intellectual property as a business asset, and African home decoration design, among other things.

You can also access most of the content from these magazines online, but I'd like to suggest stopping by the Patent and Trademark Center to browse the titles on the shelf. Perhaps you'll be inspired.

Sunday, October 12, 2008

New invention promotion TV ad channels Lionel Richie

The latest in the series of spots from the Ad Council encouraging kids to invent stuff is so deadpan that I found myself buying it for a split second:

I wonder if Lionel Richie's shoes came up in the kid's prior art search:

Sunday, October 5, 2008

Trademarks gone wild in Canada?

Just as we're all winding down from this year's Olympic Games in Beijing, folks in Vancouver are making preparations for hosting the 2010 Winter Olympics.

I had some fun in this blog highlighting some Olympic trademark issues that have come up here in the U.S. over the years. According to the CBC, it appears that our neighbors to the north are also taking some legislative steps to provide extra protection for Olympic-related marks:

The committee is so serious about protecting the Olympic brand it managed to get a landmark piece of legislation passed in the House of Commons last year that made using certain phrases related to the Games a violation of law.The list includes the number 2010 and the word "winter," phrases that normally couldn't be trademarked because they are so general.

Read the whole article here.

Thursday, October 2, 2008

An excellent comparison of online patent datebases...

...is found at Michael White's Patent Librarian's Notebook blog. White is a heavy-duty patent librarian and he makes wonderful charts.

It's interesting that free patent search websites keep popping up, but, as White's comparison illustrates, nothing has really improved on the USPTO database for searching for U.S. patents.

Sunday, September 28, 2008

Copyright and the Building Code

The Chronicle reported this weekend that a Sebastopol man named Carl Malamud has taken the California Building Code and made it available at his website for free. California licenses the building code from the International Code Council, a nonprofit that creates, updates, and sells uniform codes (covering generally construction-related subjects like plumbing and electricity) to local and state governments worldwide. Unlike other codes, which are developed by people working on behalf of the government, the building codes and other allied codes are licensed; ICC retains copyright ownership of the codes.

This means that California can't put the building code online with the rest of the Code of Regulations. People are responsible for abiding by the building code, however, so they must either buy a copy from the ICC or come in to the library and use the copy that the state provides, gratis, to every California State Documents Depository library.

Some of the claims in the article are misleading; despite the cost to purchase the Building Code and a few other licensed codes, the vast majority of codes and regulations at the local, state, and Federal level are available for free online, and everything else can be found in many libraries. Even the handsome version of the U.S. Code that we have here in the library, which is bound and annotated, costs a couple of zeroes short of the quoted $6 million.

It's anyone's guess as to whether or not ICC will sue Malamud and, if they did, who would win. It's clear that Malamud is not respecting ICC's claim of copyright ownership for the code, but perhaps his argument that the code is law and law must be free would win favor in the courts. Perhaps California can renegotiate with ICC to include online access to the Building Code, or perhaps the state could create its own code rather than licensing from ICC. What do you think? Please leave comments.

Saturday, September 20, 2008

Lehman Brothers patent didn't seem to work

You'll have to forgive me if I'm speculating a bit here, but, as a patent librarian, I can't pass up such a good opportunity to illustrate a really important point for fledgling inventors.

If you pay much attention to the news, you may have noticed that major investment banks are dropping like flies. A major contributor to the economic problem has been "toxic debt," meaning, in this case, billions of dollars in mortgages that people have been unable to pay.

What you see above and to the right is the front page of a patent owned by Lehman Brothers, one of the first banks to go under, for an "Automated Loan Evaluation System." (I found this on Peter Zura's 271 Patent Blog)

Now, I have no way of knowing if anyone at Lehman Brothers actually used this system, or if it contributed to their taking on mortgages that customers were unable to pay back. Chances are, this had very little to do with the financial crisis that's the U.S. is facing right now. But still, this is like finding amidst a shipwreck a patent called "Process for Safely Navigating the Sea" or something like that.

A significant portion of the patenting process is evaluating an invention's potential to make money. It can be easy to assume, as many people do, that, in order to be patented, an invention would have to have some intrinsic value. And it's true that, in order to meet the utility requirement, an invention must be "useful." However, it's generally not very difficult to meet that requirement. As David Pressman says in Patent it Yourself (of which we've recently gotten a new edition, by the way), "It's hard for me to think of an invention that couldn't be used for some purpose."

Even a patented invention can be a commercial disaster. In fact, the rule of thumb among inventors in the know is that fewer than 10% of patents ever turn a profit for their owners. This figure is always used to illustrate the importance of doing market research before investing much money into getting something patented. It's a bummer to think that an inventor could be discouraged to pursue bringing an invention to the market by the low success rate, but it's a much bigger bummer to think about someone investing their life savings in a product that won't generate any money.

The lesson to be learned here isn't to give up on inventing because the margin for success is too narrow. Rather, before pursuing a new invention, maybe stop by the Business, Science, and Technology Desk on the fourth floor of the Main Library to do a little market research. Don't let your patent quest be a financial disaster.

Friday, September 12, 2008

Harry Potter and the Fair Use Litigation, Redux

The New York Times reported this week that the Harry Potter Lexicon, a companion book to the hugely popular Harry Potter series and an adaptation of a popular fan-run website, is substantially similar to the original books and can therefore not be published.

Back in April, I wrote about the lawsuit in this blog entry, but allow me to recap here for new readers. Essentially, the story goes like this: Steven Vander Ark, a fan of Rowling's work, created a popular website called the Harry Potter Lexicon, in which fans contributed facts about the characters, settings, plots, etc., of the Harry Potter novels. The end result was a fairly comprehensive guide to the series. Rowling herself actually praised the site. However, when Vander Ark adapted the site to create a book, Rowling (and Warner Bros., who produces the Potter movies) sued the publisher of the book to block the Lexicon's publication. A Federal judge in New York ruled on Monday in favor of Rowling and Warner Bros., blocking the publication of the book and awarding the plaintiffs $6,750 in damages.

The problem, as the judge saw it, was that the new work was just too similar to the original work to be considered a transformative use of that work, meaning that, rather than using Rowling's work as a jumping-off point for an original work, Vander Ark simply took her ideas and rearranged them.

Literary companions are generally considered to be perfectly acceptable, but it would seem that there were a couple of factors working against the Lexicon. First, Vander Ark apparently (the book isn't published, so I'm going by the judge's reading of it) didn't add a significant amount of new material to Rowling's work, but rather just put it into a different order. According to the Associated Press story about the ruling, the judge does not wish to discourage the creation of reference books to help readers of the Harry Potter series; there just wasn't enough new material in the Lexicon. Second, while Rowling applauded the non-commercial website version of the Lexicon, the book would have likely been somewhat commercially successful; fair use arguments often hinge upon using material for educational or non-commercial uses. Rowling had apparently discussed collaborating with Vander Ark to create a Harry Potter encyclopedia, but had decided to create her own instead. Considering all of this, it isn't surprising to me that she filed suit.

What is surprising is Vander Ark's persistent fanaticism about all things Potter. The Times reports that he is carrying on with plans to publish a Potter-themed travel memoir, and that he cried during his testimony because he feared he had incurred the wrath of the Harry Potter community. He reportedly has no hard feelings towards Rowling.

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

IP in the News: GOP taking some heat over copyright

While I was looking for some information to update my previous post about the Presidential candidates' positions on intellectual property, I came across this story on Wired News.

It appears that the GOP has received a cease-and-desist notice from rock band Heart's management after playing the song "Barracuda" publicly at the Republican National Convention on Thursday, allegedly without permission. The band posted this note about the incident on their website.

According to the Wired piece, this incident follows a couple of objections to the McCain campaign's use of music for advertisements -- Jackson Brown has filed suit alleging infringement in the use of one of his songs in a campaign commercial, and YouTube removed a campaign video featuring a Frankie Valli song at the request of Warner Brothers.

Friday, September 5, 2008

Food, or rather drink, for thought

I'd say the staff in the Government Information Center represents a pretty fair sample of San Franciscans as a whole, and, as such, we have among our ranks several restaurant enthusiasts. That explains how an interesting intellectual property quandary came to my attention recently.

Here's the scene: there's a hot new restaurant in town, and much of the buzz surrounding the restaurant emanates from a renown bartender who has come up with some edgy cocktails to complement the restaurant's largely experimental menu. The fledgling restaurant seems to be getting a boost from people who want to taste this bartender's signature drinks.

Now, judging by the portrayal of the restaurant business based on what I've seen on TV dramas (admittedly not the most reliable source of information, but what am I, some kind of librarian?), the kitchen of a hot dining establishment is a pretty high-stress place. It wouldn't be surprising, then, to learn that said bartender has parted ways with the restaurant.

And now for the intellectual property question: can the restaurant keep serving the cocktails?

In this blog, I've already discussed at length the difficulties surrounding intellectual property and foodstuffs. The same would probably go for drinks. It's tricky to satisfy the non-obviousness requirement for a patent when the invention is a combination of known ingredients. To qualify for a patent, the result would have to be surprising to a person with reasonable skill in that area. That would mean that the combination of ingredients would have to be be surprising to, say, a bartender. And by surprising, I don't think that "wow, this tastes like chocolate" or "I'm really surprised that this actually tastes good" would qualify. If you mix vodka, cranberry juice, amaretto and lime and it suddenly turns into breakfast cereal, maybe. But probably not.

How about copyright? The drink itself wouldn't qualify (it's not a literary, dramatic, or artistic work). The drink description, as written on the menu, is certainly under the purview of copyright. That wouldn't mean that the restaurant couldn't continue to make the drink, but, if the bartender owned the copyright to the description, they'd have to change it. But, since the bartender would have created the description in the course of her normal work duties, the employer (the restaurant) would have a pretty strong claim that it was a work made for hire, meaning the employer would own the copyright anyway.

There doesn't seem to be much recourse for a jilted bartender leaving a restaurant. The best way to retain control over a drink recipe would probably be to keep it to yourself. Hey, it's worked for Coca Cola for a long time.

I should note that all of this is speculation. Nobody around the office has actually heard of any bartenders or restaurant owners getting into a scuffle over improper use of a drink (which is different from people getting into scuffles over improper behavior after a few drinks).

There is, however, a lesson to be learned here. The next time someone offers you one of their "patented [insert drink name here]," you can say something like "You know, I find it highly unlikely that your cocktail, regardless of how unique and tasty it is, satisfies the non-obvious subject matter requirement adopted by the USPTO as set out in Title 35, Section 103 of US Code." You'll be the life of the party!

Wednesday, September 3, 2008

Getting closer to "Indiana Jones and the Inventor's Notebook of Destiny?"

It's about time that something came along to replace the Nutty Professor image of the inventor in popular culture.

This fall, Greg Kinnear will portray inventor Robert Kearns in "Flash of Genius." It looks like the movie is going to focus on the little-guy-versus-mega-corporation angle, so I doubt there will be much inventing in it.

Kearns' story is pretty interesting. In 1967, he patented several devices that make up intermittent windshield wipers, which have become more or less a standard feature on new cars. He shopped his invention to the Big Three and, though they never reached a licensing agreement, the wipers eventually began to appear on new cars. Kearns sued Ford and Chrysler for infringement and was awarded over $20 million in damages in the two cases. The New York Times ran a nice obituary when he passed away in 2005, available here.

Friday, August 29, 2008

Barbie, Bratz, and a lesson about works made for hire

When this patent librarian was a kid, Barbie dolls pretty much ruled the roost when it came to fashion dolls. While HotWheels had to compete with Matchbox, and Gobots wooed a loyal following away from Transformers, there was really no substitute for Barbie dolls in the imaginations and toy boxes of children.

More recently, though, Barbie has had to deal with some pretty fierce competition from a line of dolls known as Bratz. Launched in 2001, the Bratz line of dolls, with their fashion-forward outfits and grotesquely large heads, wowed their target audience and proved a major success for their manufacturer, a company called MGA Entertainment.

Bratz and Barbie have recently made headlines because of a lawsuit alleging that the original drawings from which Bratz came and the Bratz name itself actually belonged to Mattel, the company that makes Barbie. (And you were wondering what all of this had to do with intellectual property.) In July, a jury ruled that the creator of Bratz, Carter Bryant, had come up with the concept while working for Mattel and that MGA was infringing on their copyright by producing the dolls. A few days ago, Mattel was awarded $100 million in damages; as of yet, it is still unclear whether MGA will be able to continue to produce the Bratz line.

Determining authorship can be difficult in the realm of copyright, and cases like this one illustrate an important concept in figuring out who owns what. In regards to copyright, authorship refers to the creator of a given work. At its simplest, the "author" of a work is a person who put pen to paper, fingers to guitar, eye to lens, etc.

Once we get into the world of businesses, however, things get a little trickier. Intuition would tell us that Carter Bryant, the person who drew and named the dolls, would be the author and, thus, the owner of the copyright. The problem is that at the time that Bryant created the drawings and name, he was working for Mattel as a designer. Because he was under contract to design dolls for Mattel, the designs that he came up with during his employment with Mattel would be considered the property of Mattel.

This aspect of authorship is known (here comes the jargon) as a work made for hire. The idea is that if you create something during the course of employment or are contracted by an employer to do a certain type of work, the work that you create during that employment becomes the property of the employer. This blog, for instance, is part of my work as a librarian. Because I create the blog while I'm on the clock, the copyright belongs not to me but to my employer, the San Francisco Public Library. In the case of a blog made for education use by a non-profit library, the copyright isn't really valuable. But for Mattel, the Bratz copyright has proven valuable both because of the loss of revenue caused by the competition with Bratz and because of the potential revenue that the dolls could have made for Mattel had they been the firm to market them.

As a product designer under contract, Carter Bryant most likely didn't punch in and punch out like people performing other types of work would do, so Mattel probably included in his contract a statement of ownership of his doll designs during the course of his employment. Indeed, only $10 million of the $100 million award was for copyright infringement; the rest was for breach of contract.

Like just about every legal issue related to intellectual property, the rules governing work made for hire aren't always concrete. For an authoritative handling of work made for hire, check out the Copyright Office's Circular 9, which covers how to determine if a work is in fact made for hire.

Sunday, August 24, 2008

Closing the lid on Pandora?

Ever since Napster, it's been anybody's guess as to how (or if) music distributors can deliver media to listeners in a way that is satisfactory to both consumers and people with a financial stake in industry. The industry has made it clear that they will enforce their copyrights, and, with the support of the Federal government (particularly via the Digital Millennium Copyright Act), has tended to favor pretty strict control over the use of their protected materials.

One solution that has, at least up until now, seemed to be working was using the radio format to play music over the internet. For many years, record companies and artists have relied on performance rights organizations to streamline the licensing process so that copyright owners can profit from radio broadcasts of their songs. These groups (in the U.S., it's ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC) are responsible for setting royalty costs for radio play, keeping track of who played which songs on which station, and getting payments from radio stations to copyright holders.

Sound Exchange is the organization responsible for managing digital broadcasts, including Internet radio broadcasts. The Washington Post ran an interview last week with Tim Westergren, founder of a very popular Internet radio site called Pandora, in which he discusses the effect that recent royalty hikes have had on the otherwise successful startup.

Pandora takes a unique approach to radio broadcasting in which listeners can create personal radio stations that play songs that match their taste. Listeners can enter a song or artist that they like, then the radio station will try to play songs that have similar characteristics. The data about the songs comes from a related project called the Music Genome, in which analysts assign characteristics to describe songs. The idea is that each user can start with something that they know they like, then play music that is musically similar, but which they may not have otherwise found. Pandora makes its revenue from advertising on the website.

If you'd like a musical background while you ponder the ramifications of digital media on the world of intellectual property, you may want to try Pandora sooner rather than later, for Westergren claims that the new, higher royalties are taking their toll on his company's profits and it may soon have to pull the plug.

It's been fun, at least for IP nerds like myself, to watch intellectual property policy evolve to meet the demands of new technology. If Pandora's royalties bills are too high and it has to go away, I wonder who might step up next to deliver free music over the Internet.

If digital copyright issues are of interest to you, there is no better place to start reading than the Stanford Copyright and Fair Use Center, where you will find a real feast of thoughtful commentary, links to all sorts of copyright sources, and an excellent copyright primer contributed by NOLO Press.

Thursday, August 14, 2008

Patent fees revision, effective October 8, 2008

Just in case you missed the Federal Register this morning, the Department of Commerce announced that patent fees for the fiscal year 2009 will be increasing a bit.

Fee increases are based upon the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers.

Click here to read the notice. Table two compares the current fees with the adjusted fees for small entities; these are the fees that usually apply to independent inventors and non-profits.

Wednesday, August 13, 2008

This ain't your Mr. Coffee

This patent and trademark librarian enjoys a cup of coffee now and again. And again and again. In fact, this eye-opening beverage has become part of my daily routine, and over the years I've tried a few contraptions to get more flavor out of the beans. I've tried grinders, French presses, stove-top espresso makers, percolators, and even, in a time of desperation, made some cowboy coffee.

The process of coffee making is simple enough -- add ground up roasted beans to water, heat, remove the grounds to the best of your ability, and enjoy -- and I was a bit surprised to learn of a major technological innovation in the coffee field. But leave it to our java-loving West Coast neighbors to the north to come up with a high-tech, computerized, $11,000 coffee maker called the Clover.

The Clover isn't a one-off, jewel-encrusted show piece. It's a purely functional commercial machine that just does one thing -- make coffee.

It is apparently no joke, either, if one can judge by the demand for both the expensive machine and the expensive cup of coffee that the machine is capable of cranking out. According to Mathew Honan, who wrote a piece about the Clover for Wired Magazine, there are about 250 of these things in operation. At the moment, the Clover is almost exclusively found in independent coffee shops in cities around the country. But that's all about to change -- Starbucks bought Coffee Equipment Company, manufacturers of the Clover, and will no longer sell machines to anyone. The only place new Clovers will be shipped will be Starbucks locations. I'd recommend reading Honan's piece to get the whole scoop. There's also a cool video of the Clover in action.

Wanna-be inventors should take note. The coffee machine is kind of like a modern-day mousetrap; it's ubiquitous, performs a simple task, and would appear to have been perfected long ago. Appears that way, that is, until someone takes a closer look at it. Granted, the Clover inventors were Stanford-educated product designers, but that doesn't take any gravity away from the awesomeness of their invention. I don't know how much Starbucks paid for the company, but even before that deal they'd sold 250 coffee machines at $11,000 each, which is $2.75 million worth. What a pay day! All for a coffee maker! I'm never going to look at my current coffee rig(I got it for $3.99 at Thrift Town) the same way!

The patent for the Clover hasn't actually gone through yet, but I'm going to guess it's likely to be granted. (Starbucks probably wouldn't have bothered to buy the company if their attorneys thought that they could produce the machines themselves.) Take a look at the application here and marvel at its technology. You can also follow the patent prosecution process by using Public PAIR.

Should the Coffee Equipment Company have resisted selling to a corporate giant? Is it ethical for Starbucks to keep this technology to itself? Can the success of an invention be measured by the amount of money it pays? I'm not even going to go there. I'll leave that to the other bloggers. I haven't tried the coffee yet, either, so I can't even posit an opinion on how it tastes.

For our purposes here, the Clover is a lesson in looking creatively at the every day objects in our lives. The heart of the patent system is the dissemination of technology, and every technological advance builds on the earlier work of others.

If you're a local reader and you're curious about the coffee (how could you not be?), Ritual Roasters is the only cafe in town where you can try Clover coffee. That will probably change when Starbucks puts their new acquisition to work.

The image used in this post courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

Thursday, August 7, 2008

USPTO reconsiders Dell trademark, bloggers rejoice!

Internet News (among many others) reports that the USPTO has gone back on its decision to allow Dell Computers to register "Cloud Computing" as a trademark for a line of server products.

Internet News (among many others) reports that the USPTO has gone back on its decision to allow Dell Computers to register "Cloud Computing" as a trademark for a line of server products.

Dell submitted a registration application in March of 2007 and was given the go-ahead by the USPTO in late July of 2008. On Tuesday, the USPTO canceled the Notice of Allowance, effectively reversing their decision that the trademark was valid.

Most of the coverage of this issue has been via bloggers, bemoaning what they see as a trend towards allowing companies to get intellectual property protection (patents and trademarks, specifically) for things (inventions or phrases) that are commonly in use or just plain obvious. It's fascinating stuff, and I'd recommend following this link to read all about it.

I'd rather not voice my opinion on such matters in this space. Instead, I'd like to highlight some of the opportunities for learning about trademarks that this story presents, which I've done in easy-to-digest bullet points below:

- Public opinion does count in trademark registration, although it's unusual for the USPTO to take back a permitted mark. Trademark applications are published, as are patent applications, for public scrutiny every week in the Trademark Official Gazette. (Published patent applications are available online as well.) Generally speaking, the time to speak up about a trademark application that you don't like is any time up to 30 days following publication. My guess would be that the intense media scrutiny caused the USPTO to reconsider.

- Even if the mark were registered, it could be challenged in court. The consensus seems to be that using the term "cloud" as a metaphor for the internet is pretty common knowledge. If Dell's registration would have gone through and somebody would have challenged it in court, a judge may have decided that the trademark was too obvious, in which case it would have been thrown out. It happens every so often that a brand name becomes so thoroughly adopted in popular language that its trademark no longer identifies the provider of the good or service, but only the service, and the company loses its mark. That's how in 1950 "Escalator" became "escalator."

- You can track the status of a trademark registration online. It's in the best interest of the USPTO to make trademark applications as accessible as possible -- every potential mark that is contested before registration is a mark that won't show up in the courts later on down the road. You can track the whole lifespan of a trademark registration online at the USPTO website using TARR, Trademark Application and Registration Retrieval.

Friday, August 1, 2008

My favorite is "Olympigs"

As usual, I scooped the Wall Street Journal by a few months with my report on the Congressional trademark protection given to the Olympics Committee. In all fairness, their story is, er, better, and thus perhaps worth a click.

Sunday, July 27, 2008

"My invention consists in the arrangement of two wheels, the one directly in front of the other..."

I can't think of any technological advancement more simple, elegant, and useful than the bicycle. With all of the bicycle-related-events going on this summer abroad and here in San Francisco, including a film series here at the Main Library, it's nice to see that people aren't taking the two-wheeler for granted after well over a century of popular use. This led me to wonder where the bicycle came from.

The history of technology is dotted with examples of spontaneous inventions, of people plucking inspiration from the sky and inventing something entirely new. In 1849, when New Yorker Walter Hunt needed $15 to repay a debt to a friend, he took a length of wire, invented the safety pin, and sold the rights for $400.

That doesn't happen very often. Like most lasting innovations, the development of bicycles involved a series of gradual improvements upon previous designs. The earliest vehicle that a modern person might recognize as a precursor to the bicycle is Karl von Drais' draisienne. This early 19th century two-wheeler looks remarkably close to a modern bicycle, especially considering some of the stylistic diversions later two-wheelers would take. Have a look:

Not bad for a first try, right? There are, however, a couple of things about this design that prevented it from starting a transportation revolution; most notably, perhaps, is the lack of pedals or a chain. The vehicle is propelled using Flintstone-era drive train technology.

In the 1860's, the solution to the problem of locomotion began to pop up in France in the form of pedals. At first, pedals were attached directly to the bicycle's wheel, like you see in the patent drawing below, from Pierre Lallement's 1866 "Improvement in Velocipedes:"

This design (the French called it a velocipede) represents a major step forward, but attaching the pedals directly to the front wheel meant that the bicycle was still going to be, well, rather slow. If you ever rode one of those little red tricycles as a kid, then you're familiar with this configuration -- for every turn of the pedal, you get one turn of the wheel. That means that for each stroke, the vehicle only moves the length of the circumference of the wheel, which is really tiny in the case of a little red tricycle and still small enough to inhibit fast cycling in the early velocipedes.

Although the chain transmission was around by the 1870's, the prevailing solution to the problem of the 1:1 pedal to wheel revolution ratio was to make bigger wheels which traveled a greater distance for each revolution. Thus, the "penny-farthing:" The big-wheel solution proved temporary as the metallurgical technology would catch up within the next couple of decades to enable chains and steering mechanisms, both of which pretty closely resemble the components of a modern bicycle.

The big-wheel solution proved temporary as the metallurgical technology would catch up within the next couple of decades to enable chains and steering mechanisms, both of which pretty closely resemble the components of a modern bicycle.

There was, however, one missing component that prevented the bicycle from transcending the status of amusement device to become a revolutionary means of transportation -- a comfortable ride. Early bicycles were called "bone-shakers," which gives you an idea of how people felt about riding on either solid wheels or wheels with solid rubber tires over dirt and cobblestone roads. A Scottish man named John Dunlop (last name bring anything to mind?) figured out that if he equipped his son's tricycle, the kid wouldn't get headaches from the bumpy ride. He patented pneumatic tires in 1888, and shortly began to manufacture modern tires with inner tubes. And the rest is history.

The development is a testament to the collaborative nature of technological advancement, the idea that we arrive at groundbreaking technologies like the bicycle by building on the advancements of others. There is no one bicycle patent; the bicycles that carry people to work and play are the result of hundreds of patents for gears, inner tubes, levers, ball bearings, and every other component.

We've got a pretty nice collection of books about the history of inventions, including fun titles by Umberto Eco and Tom Philbin that proved very helpful in writing this post.

Wednesday, July 23, 2008

Yeah, what he said...

Fellow patent librarian Michael White posted on his blog, The Patent Librarian's Notebook, a piece about the importance of class and subclass searching that very succinctly illustrates that, regardless of the type of invention, keyword searching won't suffice for a prior art search. I highly recommend it.

Saturday, July 12, 2008

It's All About the Bar Codes at the New Electronic Copyright Office

A couple months back, I noticed that the U.S. Copyright Office was testing online registration for basic forms. At the time, I had no idea how serious those copyright folks were about using technology to streamline the copyright registration process.

As of July 1st, forms TX (literary works), VA (visual arts), PA (performing arts), SR (sound recordings), and SE (single serials) are no longer available for download on the Copyright Office's website, which tells me that they are pushing the electronic registration system (online registration and a new super-form, discussed below) as the primary method for registration.

What does this mean for copyright registrants? Ever the amateur analyst, I've devised three categories of copyright registrants and their options for registration.

For early adapters who wish to file a basic claim

To register many of the most common types of works, users can now go completely digital using the eCO system I mentioned in a previous post. The works that qualify for the online system are those featuring what are called basic claims, meaning "literary works, visual arts works, performing arts works, sound recordings, motion pictures, and single serial issues." You know, the artsy stuff.

I suspect that one of the reasons the Copyright Office is only now rolling out online registration is that they had to figure out a way to meet the deposit requirement. Title 17 of U.S. Code, the law that establishes U.S. copyright, requires a copyright owner to hand over copies of a published work to the Library of Congress. This requirement has worked its way into the Copyright Office's policies to include any work to be registered, published or not.

Deposit of a hard copy is still required for most works, but it is still recommended that registrants file their claims online. During the online filing process, the system will generate a shipping label that the registrant can attach to the package that they will use to mail their deposit.

For some types of works, including unpublished works and electronic-only works, an online deposit is sufficient. In either case, the fees are reduced to $35 to reflect the reduction in man-hours required to process registrations.

For those who respect the efficiency of the computer-based application but still consider the tactile experience essential to registering copyright

The Copyright Office has developed a new form, called form CO, that can be used to register literary works, performing arts works, visual arts works, motion picture works, audiovisual works, sound recording, and single serial issues.

This new super-form generates bar codes as you type, which means that an application can be read by a machine for faster processing. I tried one out and was very amused. Using this method to file still costs $45, but I'm guessing it will greatly speed up the registration process, plus it takes the guess work out of choosing a form. Form CO can be used in place of forms TX, VA, PA, SR, and SE, and is the only form currently available for download at the Copyright Office website.

For the traditionalists

If you aren't ready to give up filing by hand, you don't have to worry yet: you can still get the forms, though you can no longer download them directly from the Copyright Office's website. If you fill out the electronic form linked above, they'll send you copies of the forms. We'll also keep the forms in stock here at the Government Information Center for as long as they'll keep sending them to us. There are still several types of works that must be registered using the paper forms, so logic tells me that the forms will be around for at least as long as that requirement is in place. The cost for paper registration will remain $45.

If you're still a little fuzzy about registration, check out the classic Copyright Office Circular Number 1, "Copyright Basics." As always, please feel free to get in touch with us at the Government Information Center if you'd like help figuring out your registration needs.

Saturday, July 5, 2008

Dubious Inventor Resources #1, or, Dr. Phil and the Overestimation of the Power of the Provisional Patent Application

Syndicated television talk show host Phil McGraw, aka Dr. Phil, has made a career of pushing the boundaries of psychotherapy to include finances, dieting, and, now, intellectual property.

It just came to my attention that the good doctor has published an article on his website offering his unique brand of no-nonsense advice to inventors. Phil, who "worked in litigation for years and has experience with patents and intellectual property," also calls on his buddy A.J. Khubani, a big-time infomercial producer, to weigh in on the subject.

The bulk of the advice is solid, if a little obvious, truisms such as "make a business plan," " do market research," "be patient," and the like. The kind of advice that we can all agree on -- except for one little piece of advice from Mr. Khubani that strikes me as a little misleading and potentially damaging for fledgling inventors:

“Patents are the best way to protect your idea, but they take a lot of money,” A.J. explains, noting that a patent can cost $10-30,000. “The smarter way to do it is go online — USPTO.gov — and file for a provisional patent. It cost $105, and that’s it. You’ve protected your idea.”I'm not actually interested in (read "qualified for") nitpicking all of the advice on the internet that pertains to intellectual property, but this one -- and I suspect it may have been taken out of context -- caught my eye because it reflects a potentially confusing part of the patent process that may be worth talking about a little bit here.

The problem that I see in Khubani's advice is that there is no distinction made between full patent applications and provisional patent applications, which is like making no distinction between appetizers and the main course.

Provisional patents are a relatively new addition to the inventor's arsenal, and they exist as a cheap and relatively easy way to establish the date of an invention and to tentatively protect the invention while the inventor evaluates its commercial potential. An inventor sends in a description of an invention, drawings if they're necessary to explain the invention -- and these don't have to be done to the same strict specs that full patent drawings have -- and a hundred bucks. The inventor then has a year to build a prototype, perform market research (like Dr. Phil said), try to sell the invention, and then, if all of that pans out, go to the trouble and expense of filing a full patent application.

In the old days (before provisional patent applications were given the green light in 1995) there were two ways to prove when something was invented: the inventor could either create and document the creation, with witness and all, of working prototype, or file a full patent. Neither of these options is particularly fast, nor easy to do on the cheap. Provisional patents enable inventors to take a year to evaluate their invention, and in the mean time, they can claim "patent pending" status on their invention. (Without the provisional patent application, it's illegal to do that.) If the inventor doesn't file a full patent application within a year, the provisional patent application expires, and the protection effectively ends.

And so we arrive at the point of this post -- filing a provision is not "it." For a successful invention, the provisional application is only the very beginning.

Dr. Phil seems, for the most part, to advocate a cautious approach to patenting. The provisional patent application as a first step fits nicely into this approach.

You may want to check out a couple of books that we have here at the library if you're interested in protecting an invention. Not that I think Dr. Phil is overstepping his area of expertise. Hey, if David Pressman wrote a self-help book, I'd probably buy it for the collection.

Monday, June 30, 2008

The Foundation of the U.S. Patent System

Inscribed above the front door of the Department of Commerce building in Washington, D.C. is a quote from Abraham Lincoln that neatly sums up the role that patents have played in developing the industry and commerce that have come to define the United States as we know it:

Inscribed above the front door of the Department of Commerce building in Washington, D.C. is a quote from Abraham Lincoln that neatly sums up the role that patents have played in developing the industry and commerce that have come to define the United States as we know it:

THE PATENT SYSTEM ADDED THE FUEL OF INTEREST TO THE FIRE OF GENIUS

Patents have been with us almost since the United States' inception and have acted, as Lincoln eloquently points out, as an incentive to innovate. It may be useful, then, to pause between bites of hot dog and fireworks shows this Independence Day to take a look at the genesis of the patent system in the U.S.

The power of Congress to establish a limited monopoly for inventors was laid out in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution:

To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries;When George Washington signed the Patent Act of April 14, 1790, the burden of examining patent applications landed on a three person panel consisting of the Secretary of State, Secretary of War, and the Attorney General.

The first patent was granted July 31, 1790, to Samuel Hopkins of Philadelphia. Though the handwritten document looks pretty primitive compared to a modern patent, you can see the basic elements are there: a description of the invention (it was a new method for making something called pot ash, a material in the soap-making process), an affirmation that it was new and useful, and the granting to the exclusive right to use and sell the invention to the inventor and his heirs for a specified term (14 years at the time).

Try to imagine Condaleeza Rice, Michael Mukasey, and Robert Gates scheduling time every day to examine patents. After three years, Thomas Jefferson, Henry Knox, and Edmund Randolph found that examining applications and mediating interferences (when two people apply for the same or similar patents at around the same time) took up too much of their time. In 1793, Congress passed a revised patent law with a much more lenient process in which patents were registered without being examined.

It wasn't until the Act of July 4, 1836 that examination was restored. This act more or less established the modern patent system, in which the Commissioner of Patents, who was appointed by the President with Senate confirmation, led an office of examiners who would determine the usefulness and novelty of an invention. 1836 is also the year that patents were first numbered; the older patents have an "X" before their numbers, which were assigned retroactively.

There are some pretty great stories from the early days of the Patent Office, like where William Thornton, an early Superintendent, laid such a guilt-trip on the British soldiers burning Washington D.C. in 1814 that they spared the building in which the patent models were stored.

For those with any interest in the history of patents in the U.S., we have a couple of books here at the Patent and Trademark Center. (We also have a full run of U.S. patents, which itself is an astounding historical document.)

When you're lighting your hand-protector-equipped sparkler at your Independence Day celebration this year, don't forget the role that inventors played in the early years of the United States.

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

Patents -- Where are the forms, and how much does it cost?

If you've ever done business with any government entity in the U.S., you've probably learned very quickly how things tend to go. In my experience, there are two components that define a transaction with any office affiliated with any government -- a form or several forms, and a nominal fee.

Need a dog license? Owe taxes? Want a passport? Fill out the paperwork, cut a check, and be on your way.

It follows, then, that I, as a sort of go-between for people and the USPTO, am very frequently asked where the forms for patents can be found and how much it costs to apply for a patent.

The forms are simple enough to find: we have or can get copies of all of the forms for photocopying here at the library, and all of the forms are available for download from the UPSTO website. It's important to remember, though, that filing a patent application involves much more than filling out a couple of forms. To quote the USPTO brochure A Guide to Filing a Utility Patent Application, "a patent application is a complex legal document." Click on the link to that brochure to get an idea of the parts of a complete utility patent application.

Estimating the cost of filing can be a little more complicated. Since no two patent applications are the same, the USPTO has created a sort of patent application menu, with different costs associated with different parts of the application.

To help you figure out how much you need pay, one of the forms that applicants need to fill out, called a Fee Transmittal, is a sort of checklist that you can match to the fee schedule (the official name for the menu referred to above).

If you take a look at the Fee Transmittal, it kind of resembles an income tax return -- you fill in certain values on certain lines, add or multiply other values depending on your application, then enter new values on new lines with new variables with the goal of arriving at a specific amount which you owe. (Unlike tax returns, you will always owe something.)

Also like your taxes, it's very important that you take the time to calculate your fees, check your calculations, then maybe check them again before sending in your application. If you make a mistake and send too little, you may have to pay a surcharge and your application prosecution may be delayed.

All of the above really only gives a taste of the process of applying for a patent, but my goal here, as at the reference desk, is to help people gather all of the information and materials necessary to start the process. I suspect that to many novice inventors, it comes as a surprise that there is more to obtaining a patent than filling out a form and writing a check.

It's worth noting, then, that there is plenty of help out there for people who are ready to apply for a patent and would rather not hire an agent or attorney to prepare the application. I've recommended before, and will continue to recommend, David Pressman's excellent Patent it Yourself, which walks you through all of the steps in great detail. The USPTO also has a very helpful customer service line; if you need help with your application, you can call 1-800-PTO-9199, then select option 2.

And, as always, you can get in touch with me or any of the librarians at the San Francisco Public Library Government Information Center.